Controversial surgeon, politician, benefactor & founder of the Beaney Institute

James Beaney (Image 1) was born on 15 January 1828, the third of four children born to George Beaney (labourer or in later life sawyer) and his wife Sarah née Snoad. The Beaney family lived in Northgate Street, and their children were baptized in St Mary Northgate church. Whilst James’ older brother followed his father as a sawyer, James held successive posts in the 1840s as a ‘surgery boy’ and dispenser’s assistant first with a Mr Purvis in Palace Street, then with Dr George Rigden in Burgate (Images 2 and 3), and later with Dr William Cooper, surgeon and brother of Sidney Cooper, the renowned Canterbury artist. By 1841 James as a 13 year old was living with his widowed mother and brother – his father had died in 1830 aged only 26. Much of the next decade is less well documented – various sources mention a period of poor health (probably TB), a year in Victoria in Australia helping in a chemist’s shop, return to UK and MRCS medical qualification at Edinburgh, army service as an assistant surgeon in Gibraltar and with the Turkish contingent in the Crimean War. What is more clear is that James married Susannah Griffiths in Monmouthshire in 1847, and on census day 1851 (mothering day) was with his mother visiting his married sister Mary in Bekesbourne.

James and Susannah emigrated permanently to Australia in 1857. Over the next 30 years James established himself as the most successful and probably the richest surgeon in Australia. Successes included the publication of the first Australian medical text book (1859) and advances in paediatrics; family planning; child surgery, and treatment of sexual and genito-urinary disorders. He also had some political impact in the 1880s, becoming a member of the Victorian Legislative Council. Against this, Beaney was widely disliked and ridiculed. Known as ‘Diamond Jim’ through his extravagant display of gold and jewels, he was regarded by many contemporaries as ‘egotistical, ostentatious and crass’. He was charged with murder in 1866 over the death of barmaid following an abortion, but charges were later dropped. Some claimed that Beaney had lied about his medical credentials and experience – for example in his claim to have been a Crimean veteran. Others suspected that some of his growing wealth came from illegal abortions. His detractors, of whom there were many, poked fun at his physical appearance – ‘a short, podgy man’ with an odd hair style swept ‘like a pair of horns’. Little is known of his wife Susannah. We don’t know how they met but she came from a Monmouthshire farming family and died in Bristol in 1878 during one of Beaney’s return visits to UK. They had no children.

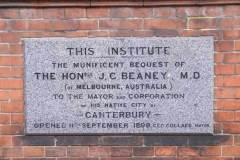

James died in 1891 in Melbourne from a brain condition. Beneficiaries in his will included Canterbury Corporation, which received £10,000 to build the Beaney Institute, currently under major refurbishment and extension (Image 4). The Cathedral received £1000 for repairs, on condition that a Beaney memorial should be set up. The apparent absence of any mention of some of his surviving family members, was judged to be less charitable. The undoubted vanity of allusions to the good Samaritan in the grandiose cathedral memorial seemed an accurate reflection on this aspect of a remarkable life (Images 5-7). Adverse comments led the Dean and Chapter to revise their policy on donations of this type – in future memorial tablets would be small and restricted to text explaining how the donation had been used. Despite the critical comments above, Beaney remains an individual born in Canterbury into poor family circumstances, with no father from the age of two, who managed by his own efforts to rise through a successful medical career, and who became a major benefactor to many deserving causes.

Sources: Thanks to Alan Barber for information and advice on sources; Australian Dictionary of National Biography (available on line); Bateman (2001) for Dispensary photograph; Kentish Gazette 7 July 1891 for Beaney obituary; Medical Times and Gazette 7 November 1863; Pearn (2004)

Update (30 October 2012): the Beaney Institute reopened to the public on 5 September 2012

DL