Until the Late Middle Ages church floors were simple. At first the building usually had an earthen floor, a generic term for a surface made from easily sourced materials such as a beaten clay or rammed chalk. Later floors may have been upgraded with a spread of mortar. If suitable stone was available locally and was affordable then a stone-flagged floor was laid. Reeds, rushes or straw were commonly laid on church floors and provided much needed insulation and a welcome contrast to the usual cold surface. To provide a more pleasant smell certain fragrant plants, such as herbs, were strewn upon the floor and some astringent smelling plants known to deter insects such as fleas were sometimes added. Periodically, perhaps two or three times a year, the rushes were refreshed.

The wealth of Canterbury Cathedral permitted the early introduction of a stone-flagged floor – known from the eleventh century nave floor – a rare luxury at the time. Some of the floors of the church building east of the crossing are likely to date from the late twelfth century. Many of the stone slabs will have subsequently been raised, and probably several times, since being laid down. This was in response to changing use of the liturgical space, including the laying of lengthy runs of central heating pipes, indoor burials (a practice accepted since the Conquest), and the natural deterioration of the floor surface through constant use.

The introduction of floor tiles in the 13th century is a feature of many monastic churches, including Canterbury Cathedral. They were preferred because they were harder wearing than clay or chalk floors and much more attractive. Once the floor surface had been levelled, the tiles were laid on a thin bed of lime mortar, the same as used for the tile grouting.

Early tiles were made in wooden moulds; the design in modelled relief was impressed with a wooden stamp while the clay was still soft. The imprint was filled with clay or slip, smoothed off then glazed and baked. Yellow and brown, the predominant colours, were obtained by the addition of iron to the lead glaze. The process is believed to have been introduced from Normandy. A locally important tile industry arose at Tyler Hill to the north of Canterbury supplying floor tiles to the cathedral and other church buildings in and around the city.

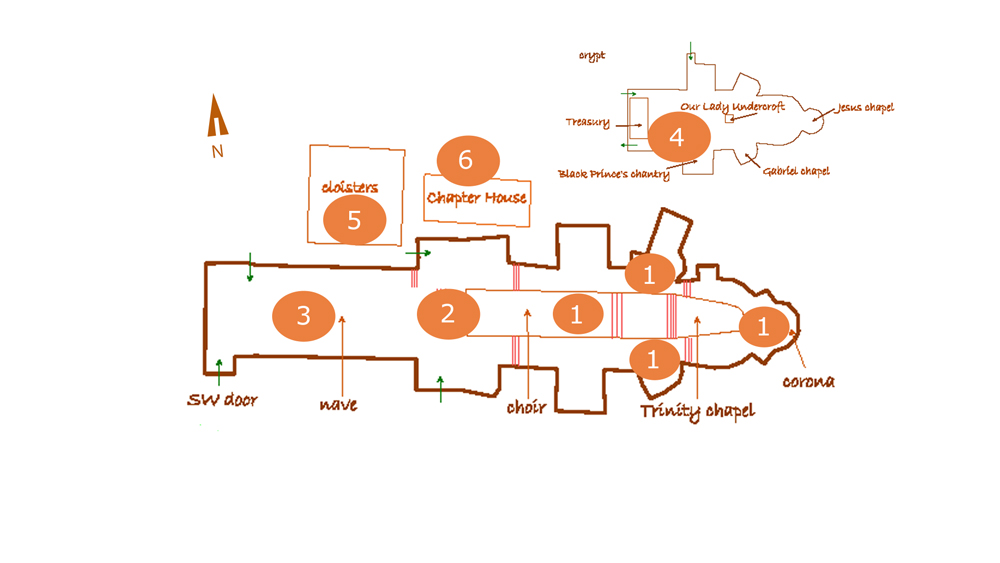

Further details have been described under six different areas of the church:

Area 1 Stones used in the paving east of the Crossing

Area 2 The Steps leading to the Pulpitum

Area 3 The Nave

Area 4 The Crypt

Area 5 The Great Cloister

Area 6 The Chapter House

Geoff Downer 2019