Basics

Geology: freshwater shelly imestone

Rock unit: Durlston Formation

Age: Lower Cretaceous

Provenance: Isle of Purbeck, Dorset

For Building Fabric

Infirmary cloister (images 1-4)

Main cloister N walk (image 5)

Corona (image 6)

SE transept (image 7)

For Floors

steps beneath the crossing (images 8-9)

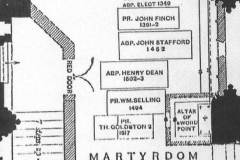

the martyrdom (images 10-12)

S choir aisle (image 13)

N choir aisle (images 14-15)

SE transept (image 16)

For Memorials

tomb of Archbishop Walter (died about 1205)

tomb of Archbishop Langton (died 1228)

tomb of Archbishop Peckham (died 1292)

tomb of Black Prince (died 1376)

tomb of Archbishop Sudbury (died 1381)

Purbeck Marble is a sedimentary rock; a limestone with a crystalline carbonate cement. The term marble is here not used in a geological sense, but instead as used by the building trade where any stone that will take a good polish is referred to as a marble. There are traditionally recognised three different beds of stone, all outcropping on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset. They are known as the Blue Marble, the Red Marble and the Green Marble; it is the Blue Marble that predominates at Canterbury Cathedral. Each of the marble beds contains numerous small freshwater snail shells of the genus Viviparus (formerly known as Paludina).

Purbeck Marble has been used since Roman times and because of its ability to take a polish it has been highly prized as a decorative stone for columns, funerary monuments and fonts. The limestone was quarried close to the coast and taken by ship from Swanage. The Crown owned many of the quarries and the first stones have been described as being taken from a shallow mine running out to sea south of Swanage. The stone became very popular with medieval masons and their patrons in the thirteenth century, especially for tall, slender and clustered columns. It was also favoured for both its ability to take a good polish and to pleasingly colour contrast with the principal building stones. Marble columns were usually cut from relatively shallow beds and consequently positioned “end-bedded”, that is to say a horizontal bed was set vertically in the building fabric. Unfortunately this could lead to failure and splitting of the stone with a consequential tendency to delaminate along the line of the bedding plane.

Later Victorian restorations indulged in coating some of the marble columns within the cathedral with various preparations, including linseed oil, presumably to protect and polish the stone. Hugh Braun the architectural historian, denounced, “The Victorian blacking which makes the shafts stand out like drain-pipes” as “a shocking desecration”. In 1931 Sir Charles Peers, the cathedral seneschal, commented: “The cleaning of Purbeck and other marble shafts in the 19th century took the form, not of repolishing, but of making up the corroded surfaces in a dark mastic composition, leaving what was left of the marble unpolished”. Many of the shafts in the east end can be seen today to bear the scars of this treatment.

Purbeck, Dorset was quarried (open-pit and underground) from discrete geological beds that outcropped east to west from the coast at Swanage inland towards Corfe. While the stone’s ability to take a good polish had long been recognised it was the period 1170 to 1540 that saw an increase in consumption of polished marble products in the form of architectural features and funerary memorials. During the mid-13th century manufacturers of effigies and tombs began to specialise and the marblers became recognised as craftsmen distinct from those masons who worked with freestone. Large prestigious commissions such as a tomb with effigy for an archbishop would have been bespoke, whilst more standard products (perhaps the tomb slab in the Mary Magdalene Chapel would be an example) were produced from pattern books or made en masse and bought ‘off the shelf’.

On the island of Purbeck a group of marblers arose, sometimes referred to as the Corfe marblers, who produced high quality items of locally quarried and polished marble. Commissions needed to take into account the bed thickness of Purbeck Marble (usually between 40 and 60cm) and with a good supply of stone and a popular product a team of workmen proficient at marketing, carving, polishing and selling the stone developed.

The precise location of the marblers “works” is still debated, but once an item was ready for conveyance, shipments departed the ’isle’ for destinations countrywide (and to France) either by way of wharfs at Wareham or via those at Swanage. Large quantities of unworked (or partly worked) blocks of Purbeck Marble, together with sizeable slabs of the stone, were also shipped to London. In the capital there was Royal patronage and other wealthy clients, both secular and religious, as well as access to a regional market. London workshops producing Purbeck Marble products including memorials developed and prospered from the 13th century and successfully competed with, or complemented, the output from Purbeck.

Many cathedrals have used Purbeck Marble in their internal decorations including Westminster Abbey and Salisbury. At Canterbury it has been used extensively in columns in the Choir and Trinity Chapel as well as in the nave and the crypt. In recent years Purbeck Marble has been worked and cut on site to replace stone columns and decorative features in the exterior facade that have weathered beyond repair. The stone usually contains a small iron content within the carbonate cement, which is liable to oxidise and rust in a wet or damp environment over long periods of time. Newly installed Purbeck Marble on the cathedral exterior may therefore have a more limited life span than most modern replacement stones, but nevertheless one extending well beyond the present century.

The texts describing the colours of Purbeck Marble differ in their naming conventions. That adopted here is the acceptance of a a blue bed, a grey bed and a green bed all containing shells of the gastropod Viviparous. Correlation of each slab to a particular bed is not always achievable as even the colour schemes can be confusing. Many of the slabs at Canterbury, notably in the steps leading from the nave to the pulpitum are red in colour. These stones are recognised as being from the green bed. The green colouration of freshly quarried stone from these beds is derived from reworked glauconite, an iron-rich mineral which is green in colour. Following installation and iron has oxidised to provide a deep red colouration. Geopetal features (see Bethersden Marble) can occasionally be found in Purbeck Marble. While the predominant fossils are gastropod shells and bivalve shells (Unio) occasionally slabs of Pubeck Marble can show more ‘exotic’ fossil remains; one stone set into steps in the south choir aisle displays several fish teeth and a broken tooth from a hybodont shark (photo available).